Mesopotamia, the cradle of civilization, wasn’t just the birthplace of writing and agriculture – it was a region where trade networks flourished and complex economies took root. From early barter systems to the rise of powerful empires, trade transformed Mesopotamian societies. Explore the fascinating world of trade, currency, economic systems, and how they shaped the legacy of ancient Mesopotamia.

KEY TAKEAWAY

- Mesopotamia’s fertile lands, combined with a lack of certain resources, spurred the early development of trade.

- Trade routes – via river, land, and sea – connected Mesopotamia with Egypt, the Indus Valley, and regions beyond.

- Mesopotamian cities became bustling hubs of commerce, with busy markets and skilled artisans producing prized goods.

- Barter systems evolved into the use of barley as a form of currency, which subsequently led to clay tokens and the birth of cuneiform writing.

- Temples and palaces played vital roles in managing resources, organizing labor, and shaping Mesopotamia’s economy.

- Empires like the Akkadians used trade as a tool for expansion, securing resources and further integrating trade networks.

- Trade’s influence reached far beyond the material realm, leaving lasting impacts on Mesopotamian art, governance, and innovation.

Mesopotamia: Birthplace of Trade and Complex Economies

Mesopotamia, a name etched in history, evokes images of fertile lands nestled between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. This vibrant region, often hailed as the “Cradle of Civilization,” wasn’t just the birthplace of writing and agriculture – it also pioneered the intricate networks of trade and economic systems that would shape societies for millennia to come.

- The Fertile Crescent: A Hub of Resourcefulness: Mesopotamia’s landscape, while rich in agricultural potential, lacked essential resources like timber, metals, and precious stones. This inherent need spurred the development of early trade networks.

- The Power of Exchange: Trade transformed simple communities into bustling city-states. It fueled innovation, craftsmanship, and ultimately, the rise of powerful empires.

The Importance of Trade in Shaping Mesopotamian Civilization

Trade wasn’t merely about exchanging goods in ancient Mesopotamia; it was a catalyst for a profound transformation that touched every aspect of life:

- Growth and Prosperity: Mesopotamian cities thrived as centers of commerce, attracting skilled artisans, merchants, and resources from faraway lands.

- Cultural Exchange: Trade routes became conduits for the exchange of not only goods but also ideas, technologies, and artistic influences.

- Rise of Writing and Record Keeping: The need to track transactions, debts, and inventories led to the development of cuneiform writing, one of the earliest writing systems in the world.

- Complex Governance: Trade necessitated the emergence of laws, regulations, and administrative systems, paving the way for complex systems of political governance.

Let’s Embark on a Journey…

This guide will delve into the fascinating world of trade and economy in ancient Mesopotamia. We’ll explore:

- Early trade practices

- Goods exchanged across vast distances

- The evolution of currency and economic systems

- The impact of trade on Mesopotamian society and its enduring legacy

Early Trade and the Seeds of Commerce:

The Ubaid Period: Local Trade and Barter Systems

The fertile plains of Mesopotamia witnessed the earliest stirrings of trade during the Ubaid Period (c. 5000-4100 BCE). While communities were largely self-sufficient, local exchange networks began to form. Farmers traded their surplus grain for essential crafts like pottery or tools.

- Barter Beginnings: Direct exchange of goods was the norm – a bushel of barley for woven baskets, obsidian blades for livestock. No standardized currency existed yet.

- The Value of Craftsmanship: Skilled artisans bartered their creations for foodstuffs and other needed goods.

The Uruk Period: Rise of Long-Distance Trade Routes

The Uruk Period (c. 4100-2900 BCE) revolutionized Mesopotamian trade. The rise of cities like Uruk fueled a need for resources far beyond local boundaries. Adventurous traders embarked on extensive journeys to procure exotic goods:

- Beyond the Horizon: Trade routes stretched across the Persian Gulf, into the rugged mountains of Anatolia, and perhaps even into the Indus Valley.

- Seafaring Ventures: Early Mesopotamian boats likely navigated coastal regions, facilitating trade in heavier goods like timber and stone.

The Early Dynastic Period: Mesopotamia’s Economic Boom

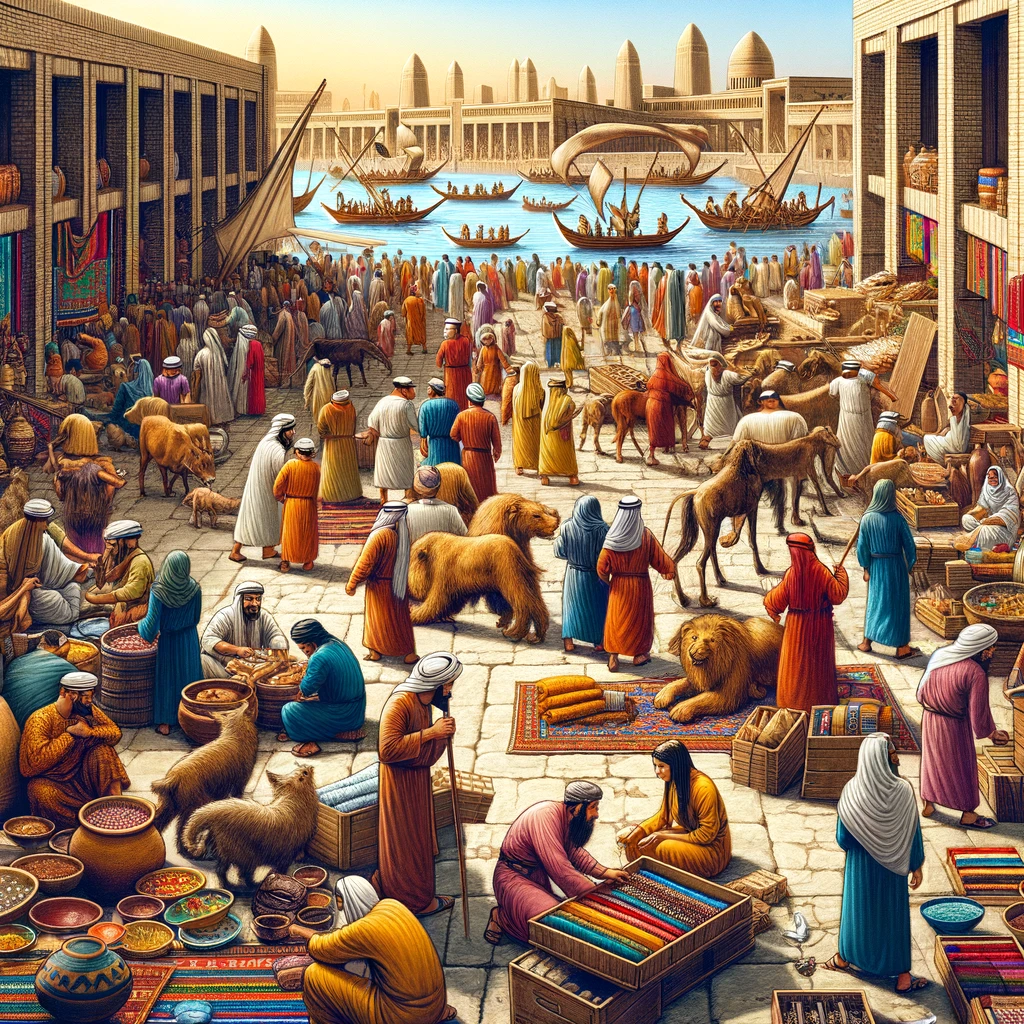

By the Early Dynastic Period (2900-2334 BCE), Mesopotamian trade blossomed. City-states became hubs of commerce with bustling markets and specialized workshops.

- Temple Economies: Temples played a central role, often storing surplus goods and acting as redistribution centers for the community.

- Growing Complexity: Trade deals became more sophisticated, perhaps even involving credit systems and early forms of written contracts.

Mesopotamian Trade: What Did They Exchange?

Mesopotamian Exports: Grains, Textiles, and Craftsmanship

Mesopotamia’s fertile lands and skilled artisans provided a wealth of goods sought across the ancient world:

- Grains of Life: Barley and wheat were staples, traded as far as Egypt and the Indus Valley.

- Fine Fabrics: Mesopotamian weavers were renowned for their textiles, particularly woolen garments.

- Craftsmanship of Quality: Metalwork, pottery, jewelry, and intricately carved seals were prized trade items.

Mesopotamian Imports: Precious Metals, Stones, and Exotic Goods

Mesopotamia’s natural resources were limited, driving their desire for imports:

- Lustrous Metals: Gold, silver, and copper were sourced from Anatolia, Iran, and perhaps even Oman.

- Gems and Stones: Lapis Lazuli (deep blue), carnelian (red), and other semi-precious stones arrived from distant lands.

- Exotic Treasures: Timber from the Levant, ivory from Africa, and exotic woods were highly valued luxury goods.

Key Trade Partners: Egypt, the Indus Valley, and Beyond

Mesopotamian traders forged crucial partnerships across the known world:

- **Egypt: ** A steady exchange of Mesopotamian grain for Egyptian gold and linen.

- Indus Valley: Evidence suggests trade links with the Harappan civilization – Mesopotamian seals found in Indus cities!

- Beyond: Trade likely extended to Anatolia (modern-day Turkey), the Levant, and possibly the Arabian Peninsula.

The Infrastructure of Trade

Trade Routes: Rivers, Land, and Sea

Mesopotamia’s network of trade routes was the lifeblood of its economy, connecting distant lands and facilitating the flow of goods:

- Mighty Rivers: The Tigris and Euphrates, the cradle of Mesopotamian civilization, served as vital transport arteries. Goods were loaded onto barges and rafts, carried by the current.

- Desert Caravans: Donkeys were the workhorses of overland trade. Caravans plied dusty routes, braving danger to bring exotic goods from the mountains and deserts.

- Maritime Ventures: Mesopotamian seafarers, likely with the help of sails, navigated the Persian Gulf and potentially reached India’s shores, expanding the reach of trade.

Key Trade Centers: From Eridu to Dilmun

Certain cities rose to prominence as hubs of commerce, where merchants from all corners congregated:

- Eridu: The Ancient Port: One of Mesopotamia’s earliest cities, Eridu, located near the Persian Gulf, was likely a crucial port in the early days of trade.

- Uruk: City of Innovation: The bustling metropolis of Uruk, known for its monumental architecture, became a center of trade and craftsmanship – a driving force of the Uruk Period’s economic expansion.

- Dilmun: Gateway to the East: The island of Dilmun (modern-day Bahrain) acted as a crucial trade entrepot between Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley. Ships laden with goods from both regions likely docked at its harbors.

Caravans, Ships, and the Business of Transport

Transporting goods was a complex and often risky endeavor:

- Organizing Caravans: Caravans required substantial investment – donkeys, supplies, and sometimes even armed guards to ward off bandits.

- Shipbuilding Advances: Mesopotamian shipwrights developed increasingly sophisticated vessels, from simple reed boats to larger, sail-powered cargo ships.

- Risk and Reward: Merchants faced the dangers of harsh terrain, unpredictable weather, and even piracy, but the potential for immense profit spurred them on.

Currency, Barter, and the Evolution of Economic Systems

Barter Systems: The Foundation of Exchange

Before standardized currencies, Mesopotamian trade relied heavily on the direct exchange of goods:

- Negotiating Value: Traders haggled over the relative worth of items – a sack of grain for a clay pot, perhaps, or a finely woven cloth for a measure of copper.

- Challenges of Barter: Finding someone with the exact goods you need, and who needs what you have, could be time-consuming and inefficient.

Barley as Currency: A Standardized Measure of Value

Barley, a staple grain, emerged as an early form of currency in Mesopotamia:

- Practical and Abundant: Barley was commonly grown, storable, and relatively easy to divide into smaller units.

- Weight as Worth: Traders began using specified weights of barley as payment, establishing a more standardized system for setting prices.

Clay Tokens and the Rise of Record-Keeping

The growing complexity of trade spurred a revolution in administration:

- Tokens of Value: Small clay tokens with different shapes were used to represent quantities of goods, making transactions easier.

- Birth of Accounting: These tokens were sometimes stored in sealed clay envelopes – the predecessors of written records and receipts.

- Precursor to Writing: The need to track complex transactions is believed to have played a major role in the development of cuneiform, one of the world’s earliest writing systems.

Mesopotamian Economic Systems: Agriculture, Trade, and Society

Rain-fed Agriculture and Trade-Driven Growth

Mesopotamian civilization was built on a foundation of agriculture, but trade acted as a catalyst for its extraordinary development:

- Northern Plains: Rain-fed agriculture in the foothills of the Taurus and Zagros Mountains supported early settlements and generated surpluses of grain.

- Southern Limitations: Limited rainfall in southern Mesopotamia posed challenges – trade was essential to access vital resources like stone, timber, and metals.

- Symbiosis of Exchange: Agricultural surpluses fueled urban centers, where artisans and merchants transformed raw materials, creating a dynamic economic cycle.

Resources and Specialization: From Farmers to Artisans

Mesopotamia’s complex economy supported the growth of diverse professions:

- The Bedrock: Farmers were the backbone of society, cultivating crops like barley, wheat, vegetables, and fruits.

- Masters of Craft: Potters, metalworkers, weavers, leatherworkers, and jewelers honed their skills, creating valuable trade goods.

- Merchants and Traders: Entrepreneurs organized caravans, captained ships, or ran market stalls, driving the exchange of commodities.

- Scribes and Administrators: The need to record transactions, inventories, and taxes gave rise to scribes – vital for economic organization.

The Role of Temples and Palaces in the Economy

Mesopotamia’s earliest institutions played pivotal economic roles:

- Temples: Economic Powerhouses: Temples often owned land, managed vast herds of livestock, and ran workshops, making them major centers of production and redistribution.

- Palace Administration: With the rise of city-states, palaces oversaw irrigation systems, regulated trade, and sometimes set prices, exercising significant influence on the economy.

- The Priest-King Connection: In many periods, temples and palaces worked in tandem, their powers often intertwined, together shaping economic policies.

The Akkadian Empire: Trade, Conquest, and Collapse

Sargon and Naram-Sin: Expanding Trade and Influence

The Akkadian Empire (c. 2334-2154 BCE) marked a period of political unification and further expansion of Mesopotamian trade networks:

- Uniting Trade Routes: Sargon of Akkad’s conquests brought key trade routes under his control, ensuring a steady flow of resources and tribute from across the region.

- Securing Resources: Naram-Sin campaigned to secure access to timber in the north and precious metals in the east, fueling Akkad’s continued prosperity.

Trade as a Tool of Empire

Akkadian rulers recognized the power of trade as a tool for stability and control:

- Royal Merchants: Kings sent official trade agents abroad to secure favorable deals and establish diplomatic ties with trade partners.

- Economic Control: Trade networks were leveraged to maintain influence over conquered territories and regulate the flow of essential goods.

Economic Decline and the Fall of Akkad

While trade initially helped the Akkadian Empire thrive, a combination of factors contributed to its collapse:

- Overextension: Maintaining the vast empire put a strain on resources and likely made it harder to respond effectively to internal conflicts and external threats.

- Environmental Factors: Climate change and severe droughts are believed to have disrupted agricultural production, leading to instability.

- Internal Rivalries: The Akkadian Empire ultimately fell due to a combination of external pressures and internal power struggles.

Labor, Specialization, and the Code of Hammurabi

From Farmers to Specialists: The Rise of Professions

As Mesopotamian society grew in complexity, so too did its workforce. Agriculture remained the backbone, but the need for goods and services beyond sustenance fueled a surge in specialization:

- Skilled Craftsmen: Potters, weavers, metalworkers, jewelers, and stone carvers refined their skills over generations, creating products of increasing sophistication.

- Essential Services: Builders, boatwrights, physicians, priests, and scribes emerged to fulfill the expanding needs of urban life.

- Traders and Merchants: Entrepreneurs organized trade ventures, bartered in bustling markets, and ensured the flow of goods across Mesopotamia and beyond.

Labor Systems and Social Structure

Mesopotamian society was highly stratified, and this was reflected in their labor systems:

- Social Hierarchy: Kings, priests, and wealthy landowners occupied the top tiers, while farmers, craftsmen, and laborers formed the bulk of the populace. Slavery also existed.

- Temple and Palace Workers: Many worked on lands owned by temples or palaces, receiving rations or land in exchange for their labor.

- Skilled Artisans: Craftsmen might work independently, for the government, or be attached to wealthy households, their status varying.

Hammurabi’s Code: Regulating Prices, Wages, and Trade

Hammurabi’s Code, one of the earliest surviving legal codes, provides insight into Babylonian economic regulation (c. 1750 BCE):

- Setting Standards: The Code specifies wages for various professions – from field laborers to physicians – indicating attempts to standardize and control labor costs.

- Price Controls: Laws in the Code aimed to prevent price gouging on essential goods like grain and wool during shortages.

- Protecting Merchants: Provisions regarding trade contracts, debt, and interest rates show a concern for regulating commercial activities and protecting the interests of traders.

Trade’s Legacy in Mesopotamia and Beyond

H2: Influence on Assyria and Babylonia

Later Mesopotamian empires, like the Assyrians and Babylonians, inherited and built upon the trade networks and economic innovations of their predecessors:

- Maintaining Trade Routes: Securing and expanding established trade routes remained a focus of Assyrian and Babylonian rulers to ensure access to essential resources.

- Innovation and Adaptation: These empires further refined administrative systems, currency, and trade policies.

Contributions to Art, Writing, and Governance

Trade’s impact extended far beyond the material realm:

- Artistic Exchange: Mesopotamian art reflects influences absorbed through trade – motifs, precious materials, and techniques from Egypt, the Indus Valley, and other regions.

- Birth of Writing: The need to track complex transactions was a key driver behind the development of cuneiform script, one of history’s most significant writing systems.

- The Evolution of Governance: Mesopotamian laws, including regulations on trade and commerce, served as models for later Near Eastern legal codes.

Mesopotamia’s Enduring Economic Innovations

Mesopotamia made foundational contributions that continue to shape economies today:

- Standardized weights and Measures: Ensured fairness in trade and laid the basis for later currency systems.

- Early Contracts and Debt Records: The practice of written agreements and record-keeping paved the way for modern systems of credit and finance.

- Urban Planning and Infrastructure: Mesopotamia’s cities required complex management of resources, trade, and infrastructure – concepts still central to urban life.

Conclusion

From the earliest bartering systems in the Ubaid Period to the sophisticated trade networks of the Akkadian Empire and beyond, trade served as the lifeblood of Mesopotamian civilization. It was far more than the exchange of commodities; it was a catalyst for innovation, prosperity, and the interconnectedness of the ancient world.

- Fuelling Progress: Trade allowed Mesopotamians to overcome the limitations of their environment, acquiring the resources they lacked and transforming them into a thriving civilization.

- Cultural Melting Pot: Mesopotamia acted as a crossroads of ideas and cultures, absorbing and influencing its trading partners across the Near East.

- A Legacy for the Ages: The economic systems, administrative innovations, and record-keeping practices pioneered in Mesopotamia laid a crucial foundation for the development of later civilizations.